Why Not All Graphene Is the Same: Structural Differences That Define Performance

Introduction

Graphene is one of the most widely discussed materials in advanced technology, yet its practical use often reveals a more complex reality. Materials described under the same “graphene” label can exhibit notably different behaviors once integrated into real systems- differences that become visible during testing, scaling, and long-term operation rather than at the conceptual level.

This article builds on the framework introduced in the first part of this blog series, which examined why advanced materials increasingly define performance limits across high-tech industries. Here, the focus shifts to graphene itself, exploring how structural choices introduced during synthesis and subsequent processing translate into measurable performance differences in applied contexts.

Within this broader landscape, Nanografi works with a range of graphene structures, including structurally engineered variants such as Holey Super Graphene, reflecting the diversity of performance requirements encountered in industrial applications.

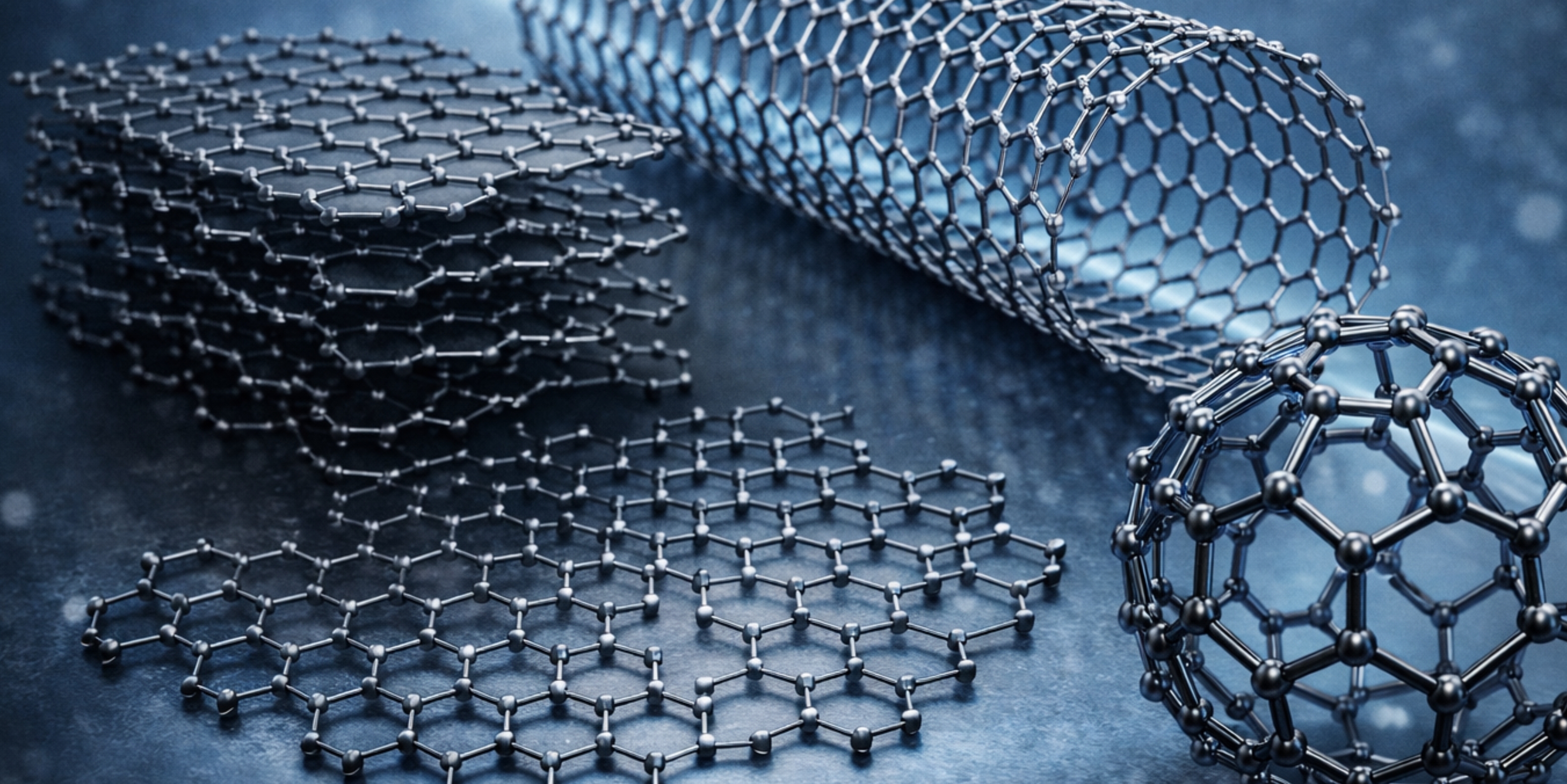

Graphene as a Family of Structure

At the atomic level, graphene is defined as a single layer of sp²-bonded carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. In practice, however, most graphene materials used in industry differ from this idealized form. Multilayer graphene, graphene nanoplatelets, reduced graphene oxide, and architecturally modified graphene variants are all widely employed.

These forms retain key graphene-derived properties while exhibiting distinct structural features that influence how they behave in real systems. Layer stacking, defect distribution, and surface accessibility all contribute to variations in electrical, mechanical, and electrochemical performance. Understanding graphene as a family of related structures provides a more accurate basis for evaluating its role across different applications.

Structural Parameters That Shape Performance

The performance of graphene-based materials is governed by several interconnected structural parameters. Layer thickness influences charge transport pathways and interlayer resistance. Defect density strongly influences conductivity, mechanical stability, and long-term durability, often introducing trade-offs between transport properties and structural integrity. Edge structure and surface chemistry determine interactions with ions, molecules, and surrounding matrices.

Internal architecture further modulates these effects. Continuous basal planes favor efficient electron transport, while the presence of edges or pores can facilitate mass transport and enhance access to active surface sites in surface-driven processes. How these characteristics are balanced depends on the intended application and operating conditions.

Porous Architectures in Graphene Design

Porous graphene architectures introduce nanoscale openings within or between graphene domains, increasing effective surface area while maintaining percolating conductive pathways. This structural approach directly influences how graphene interacts with its environment, particularly in transport-limited systems.

Experimental studies have shown that nanoporous graphene structures can support faster ion diffusion and improved electrochemical accessibility compared to non-porous graphene sheets (Bai et al., 2010; Surwade et al., 2015). These effects primarily from architectural design rather than from intentional chemical functionalization, allowing key graphene-derived properties to be preserved while expanding functional behavior.

Holey Super Graphene as a Pore-Engineered Structure

Holey Super Graphene represents a pore-engineered graphene structure developed through controlled synthesis and processing protocols at Nanografi. Its finely tuned porous architecture increases surface area while synthesis and processing protocols. This structural configuration enables enhanced charge and mass transport, which is particularly relevant for applications involving electrochemical reactions, sensing interfaces, or surface-dominated processes. The performance characteristics of Holey Super Graphene emerge directly from its internal architecture rather than from intentional changes to graphene’s fundamental chemistry.

Structural Choice and Application Context

Different graphene structures align with different system requirements. In applications where electrical continuity and mechanical reinforcement dominate, more continuous or less porous graphene architectures may be appropriate. In systems where interaction with ions, molecules, or biological species limits performance, performance through transport or surface accessibility, porous architectures can offer measurable advantages. From an engineering perspective, material selection is guided by how structural features influence system-level behavior. Evaluating graphene through this lens allows performance differences to be understood as outcomes of design decisions rather than inherent material hierarchies.

Industrial Considerations and Scale

Structural distinctions between graphene materials become increasingly important during scale-up. Maintaining pore structure, controlling defect generation and evolution during processing, and ensuring batch-to-batch consistency are essential for reproducible performance.

Research on scalable graphene production emphasizes that structural control during manufacturing strongly influences functional reliability in applied environments (Bonaccorso et al., 2012). For industrial users, this highlights the importance of considering both material architecture and production consistency when evaluating graphene materials.

Conclusion

Graphene’s impact across advanced technologies is largely driven by its structural adaptability. Variations in layer configuration, defect distribution, and internal architecture give rise to graphene materials with distinct performance profiles. Recognizing these differences enables more precise alignment between material structure and application demands.

Within this context, Nanografi develops graphene materials across a range of structural configurations, including pore-engineered solutions such as Holey Super Graphene. This structural diversity reflects the broader reality that graphene performance is defined not by composition alone, but by its engineered architecture and structural control.

In the next article of this series, the focus will move from graphene structures to evaluation criteria, examining the key performance metrics used to assess nanomaterials in real-world applications.

References

Bai, J., Zhong, X., Jiang, S., Huang, Y., & Duan, X. (2010). Graphene nanomesh. Nature Nanotechnology, 5(3), 190–194.

Bonaccorso, F., Lombardo, A., Hasan, T., Sun, Z., Colombo, L., & Ferrari, A. C. (2012). Production and processing of graphene and 2D crystals. Nature Photonics, 6(12), 819–827.

Surwade, S. P., Smirnov, S. N., Vlassiouk, I. V., Unocic, R. R., Veith, G. M., Dai, S., & Mahurin, S. M. (2015). Water desalination using nanoporous single-layer graphene. Nature Nanotechnology, 10(5), 459–464.

Geim, A. K., & Novoselov, K. S. (2007). The rise of graphene. Nature Materials, 6(3), 183–191.

Recent Posts

-

Graphene Based Neuromorphic Hardware

Introduction The most significant structural challenge of the digital age is the physical distance b …6th Mar 2026 -

Transistor - Effect MXene Membranes

Introduction Material science is undergoing a revolutionary transition from passive and static compo …27th Feb 2026 -

From Vibration to Information

Introduction Over the past decade, materials science has undergone a fundamental paradigm shift from …20th Feb 2026